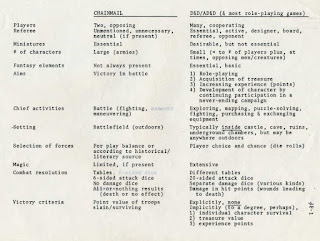

When Dave Arneson’s lawsuit against TSR was nearing a trial date at the end of 1980, his legal team recruited an expert witness in the person of Jon Freeman. Freeman, who wrote for Games magazine and had recently produced The Complete Guide to Board Games, was a longstanding D&D fan who drove one of the earliest computer adaptations of dungeon-crawling to see a commercial release: The Temple of Apshai (1979), first of the “Dunjonquest” series. Today, we’ll take a look (a layman’s look, not a lawyer’s) at Freeman’s deposition, beginning with his chart above, which shows how Gary Gygax’s earlier Chainmail rules contrasted with both D&D and AD&D.

The subject of Freeman’s deposition is related, but not identical, to the core question of Arneson’s lawsuit, which was whether the language in the 1975 D&D contract requiring TSR to pay royalties on “the cover price of the game or game rules for each and every copy sold” applied solely to the D&D ruleset published at the time it was signed, or if it further applied to later (derivative) works like the Holmes Basic Set and the AD&D game. Freeman instead looks at the more conceptual question of whether AD&D was the same game as D&D: if it were, that would bolster the interpretation of the contract that Arneson hoped to establish.

Freeman’s chart comparing D&D and AD&D to Chainmail above fairly represents points where D&D and AD&D are conceptually unified in ways that distinguish them both from earlier wargames. No one was going to argue that Chainmail and D&D (or AD&D) were the same game. Which is not to say there isn’t plenty to nitpick here, in his characterization of both Chainmail and D&D. But fundamentally, Freeman is correct that you can attribute any of the things under that second column equally to either D&D or AD&D — it’s fair to lump them together.

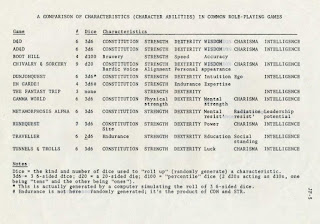

However, you could lump numerous other early RPGs under that second column as well, given how high level its criteria are. This was a talking point that Gygax advanced in Dragon magazine, that, “there is no [more] similarity (perhaps even less) between D&D and AD&D than there is between D&D and its various imitators produced by competing publishers.” To answer that, Freeman offers a breakdown of how character statistics are managed across several early RPGs:

Again, we could nitpick the chart here based on the fairly limited slice of early games it includes, but the core point is valid: AD&D used the same basic system concepts as D&D and called them the same thing, be they abilities, levels, spells, monsters, magic items, experience points, or what have you. Freeman goes on to say:

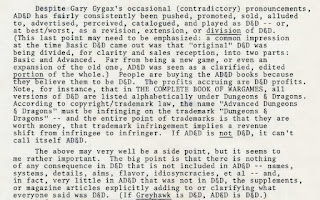

Freeman’s point about trademark here has some validity — if Tunnels & Trolls had instead called itself Ken’s Dungeons & Dragons, it would have been just such an infringement and TSR would undoubtedly have gone to court over it. But Arneson had no contractual interest in the D&D trademark, only in its copyright. Moreover, this excerpt concludes in a place that further exposes the distinction between Freeman’s conceptual analysis and the contractual question before the court. Greyhawk certainly was D&D, in any meaningful sense, but Arneson was not paid any royalties for Greyhawk, and if the case had gone to trial, you could imagine TSR’s counsel asking Freeman, “If Arneson doesn’t get royalties for Greyhawk under the D&D contract, why should he get them for AD&D?” The question of whether conceptually “Greyhawk is D&D” has no bearing on the question of whether Arneson should be paid royalties for it, of whether its cover price counted as “the cover price of the game or game rules for each and every copy sold” under the 1975 D&D contract.

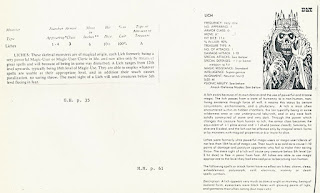

The AD&D rollout began at the end of 1977 with the Monster Manual, and Freeman argues that it marked no clean break from the original D&D system, that “monsters from the Monster Manual could be used, can be used, and were used in D&D games with no alterations whatsoever.” Arneson’s legal team spent a lot of time photocopying side-by-side comparisons of the OD&D books with AD&D, which included a hard look at the Monster Manual. Take the lich, for example:

The irony is that the lich here comes from Greyhawk, and even if “Greyhawk is D&D,” it was not something that Arneson received royalties for. When the Greyhawk supplement appeared in 1975, it added a number of new monsters (31, more than half as many as there were tabulated in the original Monsters & Treasure booklet) and moreover respecified all of the existing monsters in OD&D (via the “Attacks and Damage by Monster Types” chart). Was the respecification in Greyhawk different in kind from the respecification seen in the Monster Manual? Imagine for a moment that the Monster Manual had, per Freeman, been marketed as a supplement to OD&D… would that have made Arneson any more entitled to royalties for it than he was for Greyhawk?

Read more at this site