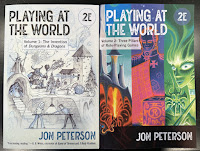

With the release of its second volume, the second edition of Playing at the World is finally complete. The two books combined total well over 1,000 pages on the conceptual origins of role-playing games. The first edition had been out of print for some years, so if you’ve wanted to check it out, this would be a good time. Each volume has a spiffy new cover by classic D&D artist Erol Otus, and of course updated coverage of its sprawling subject matter.

Reading the 2012 edition of Playing at the World cover to cover, you would first take in Gygax and Arneson’s activities up to 1973 (Section 1), then three historical deep dives into setting, system, and character (Section 2-4), followed by the immediate aftermath of the release of D&D and the birth of the role-playing game industry (Section 5). This ordering encouraged readers to “eat their broccoli,” as I sometimes put it, by absorbing a detailed histories of subjects like conflict simulation before getting to the dessert of D&D’s reception and success. This certainly was not to everyone’s taste, and I gather some diners left the table halfway through the meal.

In 2E, what were the first and fifth chapters of the 2012 edition make up the first volume, The Invention of Dungeons & Dragons. In the newly-released second volume, The Three Pillars of Role-Playing Games, the eponymous “pillars” are setting, system, and character, per the middle three sections of the 2012 original. Ironically, some of the earliest surviving outlines of PatW had precisely this organization, where the histories of system and setting were relegated to appendices after the main narrative. Hopefully this will make the work more accessible, and the core narrative of the first volume a bit more cohesive. The more scholarly bits are reserved for the second volume, including the bibliography and methodology.

The book has been reorganized but not rewritten from the ground up. Instead, it has been updated in places where scholarship has moved forward since 2012. The biggest changes cover recently unearthed draft material from the development of D&D in 1973, but there is also more detail on things like the Midgard phenomenon, the Hyborian campaign, and similar precursor and parallel activities. The book remains a thorough repository for the evolutionary history of fundamental system concepts that D&D popularized: experience points, hit points, the dialog-based interface, limited information scenarios, and so on.

So is the combined PatW2E actually longer than the original? No, it comes in at a slightly lower overall word count — though because it has been typeset by response professionals rather than myself, the page count, and shelf width, is larger.

It is in part shorter because it discarded a lot of information redundant with the more detailed coverage in my other books. Discussions of corporate finances, disputes over credit, and so on have largely been removed, as they are better covered in Game Wizards. The fledgling RPG industry of the late 1970s is now better detailed in The Elusive Shift. The brief bits about computer game history in the Epilogue of PatW1E were not very helpful and have basically been dropped, apart from an aside in V1. What remains cannot lay claim to being sharply focused: the book remains necessarily a survey of disparate activities, one that aspires to provide a comprehensive overview of how D&D came to be.

But Playing at the World cannot claim to have “solved” the history of D&D. I believe we remain in the early days of scholarship related to role-playing games, and twelve more years of work could only move the ball forward to far. I do hope the book is more useful as a resource for future scholarship than the original edition. I hope it helps capture sources, influences, and activities that might otherwise have escaped the attention of posterity. If it succeeds only in doing that, I’d be happy with its achievement.

Read more at this site