In the first installment of this series, I talked about why it’s important to design good maps. I shared pitfalls I often see in lackluster turnovers, and I concluded with a small “primer” of interesting maps from the real world to look at for inspiration.

This time, I want to look more closely at dungeon maps. I’ll touch on tasks you should seriously consider before you even start drawing, as well as a few starting details to keep in mind when you officially begin.

Purpose of the Map

The first question to answer when you make a map is, what is this map for? That seems straightforward, but it never hurts to clearly define your intentions before you put pencil to paper (or mouse to screen).

Are you providing all the details the GM needs to run an adventure? Or is it a prop for players, a discoverable item in a treasure horde? Do you intend to drop it into a VTT platform to run a game digitally? Knowing who the map is for sets the tone for everything else you do to it. It helps you decide whether beauty or information is more important, and whether realism or stylistic abstractions benefit the map more.

Creating the Map

You can make a map by hand or digitally, but in either case, start on plain paper. The plethora of options available in a fancy cartography program can feel overwhelming if you don’t already have a sense of what you’re going to create. And fiddling with the interface can divert your attention from what’s really important: conveying useful information to the GM.

As a side note, if you’re making a map for publication, a cartography program might not even be that helpful. A professional cartographer is going to redraw whatever you turn over, and a bunch of bells and whistles from a mapping program might make it harder for the cartographer to read what’s going on and render the final map in their own style (which the publisher wants for consistency throughout the book).

Basic, unlined printer paper is a fine start, because you want to sketch your map out, often two or three times, before you begin the final product. If you have a scanner, start using it at this stage. Draw a baseline first, scan and print that, then add other “layers” on top of it as you progress.

Sketching first helps you do a few important things. You can figure out how to fill the space, how to create paths from point to point, and where to leave room for a key. Sketching also lets you doodle out ideas without being intimidated by the blank canvas. It lets you get creative with special features, like pinch points, important spaces, natural barriers, and elevation changes. It gives you a chance to plan out territory for different factions, or parts of the dungeon that are initially sealed away. It lets you think about negative space, the places between the dungeon rooms, and what might be hidden there. If you are working on multiple maps for several dungeon levels, it helps you line up pathways between levels so you can make them accurate later.

Who Lives Here?

As you sketch, think about what creatures you plan to include on your map. Do they belong in the space you’ve given them? All too often, I receive maps with small rooms and Large creatures inside. A GM who runs that encounter has no ability to maneuver or take advantage of terrain, because the creatures are packed shoulder to shoulder. Some creatures take up four or even nine squares on the map, and they need room to maneuver. Size your dungeon appropriately.

Wh

Here are a couple of technical points to keep in mind. If your map is going on a VTT platform, secret pathways of lower or higher elevations running under or over areas of your map are going to be trouble. Some platforms don’t have a great way to keep that part hidden from the players while they explore the main level. If you have the option of creating a separate map layer with hidden information on it, go for it, but plan ahead to provide a version where the hidden parts stay hidden.

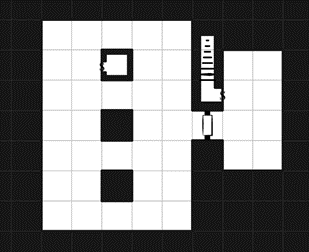

Here’s an example. In this case, the digital version should have the passage with the dotted line and the “S” on a layer that can be turned off.

Similarly, isometric maps look amazing, but they don’t work well on VTTs yet. Unless a publisher specifically asks for an isometric map, avoid the temptation. If you’re drawing for your table, of course, go for it!

Fantasy Vs. Reality

We’re making maps for a fantasy game, so it’s not only all right, but expected that some aspects of the place we’re visually describing don’t obey the laws of physics. But break those laws on purpose. Otherwise, try to create realism in your dungeon maps. For example, it’s exciting to depict a place where water flows uphill (or even up a wall!). Two or three encounters in your dungeon can be built around such an odd and clearly magical feature. But unless the whole theme of the dungeon involves reverse gravity a backward time or something, keep the rest of it flowing downward. Fantastical things only seem fantastical in comparison to the ordinary. Leave plenty of ordinary in so the magical stuff pops.

Walls are a common place where map makers break reality. Walls need thickness. If your wall is stone, but represented by a thin line on a grid separating two 5-foot squares, how thick is it? Can the barbarian smash down a 1-inch thick wall?

Add columns when rooms are large. Tons of rock and earth loom overhead. Load-bearing columns at regular intervals offset that. Even a modern office building with an open floorplan has columns set up to reinforce the integrity of the structure.

Thick walls and columns also allow you to hide secret passages within them, maybe including peepholes for spying. You can make them cramped and narrow, forcing characters to use the rules for squeezing to traverse such routes. You can also include other physical features within the walls, such as small chimneys for air flow, grates placed low on walls and the floor for water drainage, or mechanisms for traps and portcullises. You never know where a character using gaseous form might end up if they follow a route within the walls.

In Part 3 . . .

Next time, I’ll get deeper into how to include useful details in your dungeon map using tools and tricks that are often overlooked.

Read more at this site