In the previous installment, I talked about having a clear idea of who a dungeon map’s end user is so you can focus on providing relevant information. I also went into some detail on sketching out ideas and making sure the big points of interest are located where you need them to be. I talked about creating a sense of verisimilitude by adhering to the laws of physics—or being mindful of breaking them in specific ways.

Now, I want to dig more into the value of including useful details that are often neglected but can make a decent map great.

Read all the Good Maps articles!

All the Senses

Often, well developed dungeons include more than the physical dimensions of the spaces. Interesting details that stimulate all five senses give the place much more character and vibrancy. Air currents, sounds, light sources, and smells all combine to immerse players in the environment their characters are experiencing.

But frequently, these sorts of additions are only listed in the text. A good style guide and a competent editor can make the information easy to find (via bullet points or boldface type, for example), but the details are still obscured to the GM who is referencing the map during a session.

Even a thoroughly prepared GM might still forget that a group of singing kobolds or a glowing lantern around a corner can be noticed by the PCs out in the hallway. Too often, this information is imparted too late. “Oh, I forgot to mention that you could hear the faint sound of a waterfall when you were back at that end of the passage.” Adding this kind of information to a map can go a long way toward making a game master’s life easier.

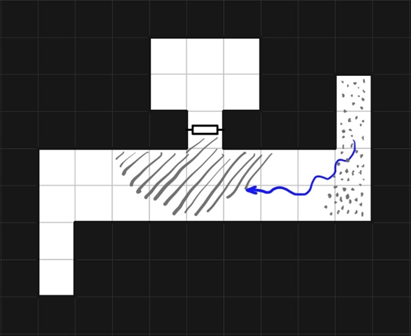

Consider the example map below, where I used visual cues to remind a GM of other sensory information:

- Gray hatching shows an area of effect for an intense smell coming from the room to the north of the door.

- Stippling to the east shows where direct light glows from a light source beyond the turn in the passage.

- a blue wavy arrow indicates the direction and relative temperature of an air current that wafts through the hall.

I created these marks freehand on my tablet in moments, and you could just as easily add them to a paper map with colored pencils. You can come up with a variety of different signifiers, such as thin or thick lines, stippling, single-direction hatching, or multi-directional cross-hatching, and different styles of line (wavy, jagged, etc.) to indicate direction of air, water, or incline of the floor.

You can even get ornate with more colors, perhaps pale purple for an odor, yellow or orange for light, and brown for some kind of sound. (Do keep in mind that some people are colorblind and have difficulty detecting red and green.)

However you approach it, adding those simple designs help a poor, harried GM remember that something special is happening there.

Conveying Other Information

In addition to sight, sound, taste, smell, and touch, you can use markings on your map to include other important details, too. Most maps already include symbols for the locations of doors and traps, but what about natural effects and hazards, such as smoke, fog, or dangerous gases? You can also show the area of effect of a permanent magical aura, where a spellcaster is likely to locate an alarm spell, the territorial boundaries of different factions of dungeon inhabitants, or anywhere there’s difficult terrain, slowing movement. All of these enhance a map’s usefulness to the GM.

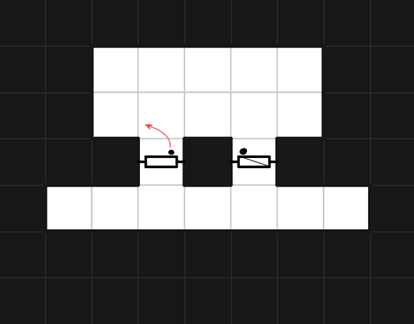

Even the standard door symbol could benefit from additional bits of information. In the example below, I’ve added a dot like a door knob on one side to show which direction the door swings (as indicated by the red arrow, which isn’t strictly necessary, but shown here for clarity). Players constantly ask how a door opens so they can judge how to use such a choke point to their advantage. So why not go ahead and include these details on your map? A diagonal line (shown on the other door symbol) can indicate a locked door. Two diagonal lines in a crisscross design can mean the door is barred, while a solid black door might convey a door that is both locked and barred, stuck, trapped, or in any other state you desire.

In Part 4 . . .

Next time, I’ll wrap up the portion of this series on dungeon maps with a look at how to make your dungeon environments interesting, getting into the weeds a bit about the creative side of mapmaking.

Dungeons Deep delivers 16 drop-in dungeons designed to fit neatly into your D&D campaign—or to quickly expand an existing dungeon of your own design. Each dungeon offers tiered monster-loadouts for low, medium, and high level PCs—so you have 48 options available!

Read more at this site